Celebrating a Man’s Life

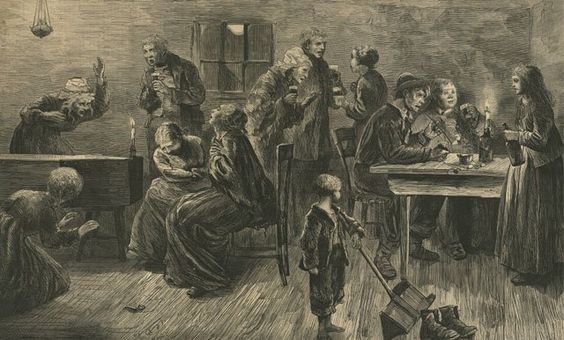

Poor Sean Maguire died, just as Mr. Roche suspected he would, and the gold and the notes were found quilted into his wretched clothing. A search was then made for any of his relatives from in and about Moneygeran. in the West of the County, where his mother was known to have lived. Meanwhile, as much was taken from the hoard by ‘Big Peter’, in whose premises he died, as was necessary to buy a shroud and coffin, and some pipes, and tobacco, and snuff. Sheets were hung up in a corner of the barn, and the poor corpse was shaved and washed, and provided with a clean shirt, before he was laid on a table in the same corner and covered with a sheet.

Two or three large, roughly coloured wood prints of devout subjects were pinned on the sheets, and candlesticks, trimmed with coloured paper and furnished with candles, were provided. One or two persons relieved each other during daylight, to keep watch and ward off any evil. Of course, any poor neighbour who was cursed with a taste for tobacco smoke was only too ready for this duty, but the approach of darkness brought company enough, more indeed than were benefitted by the social duty.

The brave old patriarch Peter rested comfortably in his own chair and was talking intently to two or three of his neighbours, as old as himself, on the old chronicles of Castleton. We had paid little attention to his legends and tales, and we are now sorry enough for our inattention. On this occasion the hero of his story was a certain Squire Heaton, who, it appears, was the possessor of the Castleton demesne in some former age, and a terrible blackguard he must have been. He was employed in some fierce argument or other with his neighbours or tenants, we cannot now remember which, about a certain common, overgrown with furze bushes. It was, in fact, a large hill, which gave shelter to hundreds of hares and rabbits, and as the Squire would not give way to the demand made on him about the hill, the party collected and set fire to it on a fine summer evening.

Big Peter described, in a most graphic manner, the effect of the fire seen from the country round and about, all the poor hares and rabbits running for their lives, with their fur all scorched, and their eyes nearly burned out of their heads, and themselves falling into the hands of the crowds that kept watch at the edge of the burning mass. This reminiscence drew on others connected with matters that had taken place before the Rebellion, and while everyone was so engaged Eddie, Brian, and Charlie entered the room, reverently uncovering their heads, and reciting the ‘De Profundis’, verse and response. At the end they put their hats back on their heads and approached the elderly group.

A granddaughter of Peter’s and Mrs O’Brien’s servant girl, Joanna, a rattling young girl, came in with them, and after the psalm joined the ‘Big Peter’s’ womenfolk in the house, who occupied seats near the table. The older people, not willing to lose any of their usual hours of rest, began to leave, after having nearly exhausted all the interesting topics of the locality. But it was not long until a considerable amount of more lively conversation, of more interest to the younger portion of the company, began to develop itself among the various groups, two or three of the chief families keeping together near the table, as has been said.

At last a request came from a young woman in this group to Mr. Edmond, that he would entertain them with a song. Never being a man that was troubled with bashfulness, he immediately agreed, merely asking one of the little boys to bring a young cat from the kitchen to walk down his throat and clear away the cobwebs. He warned his audience that his song was useful to anyone thinking of paying a visit to the sites of Dublin.

” THE CONNAUGHT MAN AT THE REVIEW.

” With a neat house and garden, I live at my ease,

But all worldly pleasures my mind cannot please.

To friends and to neighbours I bid them adieu,

And I pegged off to Dublin to see the review.

Chorus – Laddly, ta ral lal, ta ral lal, lee.

” With trembling expectations, to the town I advanced,

Till I met with a soup-maker’s cellar by chance,

Where I saw hogs’ puddings, cows’ heels, and fat tripes.

And that delicate sight

Chorus

” I stood in amaze, and I viewed them all o’er

The mistress espied me and came to her door.

‘ Step in, if you please, there is everything nice.

You shall have a good dinner at a reasonable price.’

Chorus

“I tumbled downstairs, and I took off my hat.

And immediately down by the fireside I sat.

In less than five minutes she brought me a plate

Overflowing with potatoes, white cabbage, and meat.

Chorus

” Says she, it was in Leitrim I was born and bred,

And can accommodate you to a very good bed.’

I thanked her, and straightway to bed I did fly,

Where I lay as snug as a pig in a sty.

Chorus

“In less than five minutes my sides they grew hard,

For every feather it measured a yard.

A regiment of black boys my poor corpse overspread,

And insisted they’d tumble me out of the bed.

Chorus

“I slept there all night until clear day-light,

And immediately called for my bill upon sight,

Says she, ‘as we both are come from the one town,

And besides old acquaintance, I’ll charge but a crown.’

Chorus.

” Oh, that is too much now, and conscience to boot;’

So, between she and I there arose a dispute.

To avoid the dispute, and to soon put an end,

She out for the police her daughter did send.

Chorus

“In the wink of an eye I was sorely confounded

To see my poor body so sadly surrounded.

I thought they were mayors, or peers of the land,

With their long coats, and drab capes, and guns in their hands.

Chorus

“‘Gentlemen,’ says I, ‘I’m a poor, honest man:

Before in my life I was never trepanned.’

‘ Come, me good fellow! Come pay for the whole,

Or else you will be the first man in the goal.’

Chorus

“I paid the demand, and I bid her adieu,

And was off to the Park for to see the review.

Where a soldier he gave me a rap of his gun,

And bid me run home, for the white eyes were done.

Chorus

“‘My good fella,’ says I, ‘had I you where I know,

I’d make you full Bore to repent of that blow.’

At the hearing of this, in a passion he flew,

And his long carving knife on me poor head he drew.

Chorus

There were three or four verses more, but the readers are probably content with the quantity furnished. There was clucking of tongues against palates at the mention of the roguish tricks of the Dublin dealers. But a carrier in company cleared the city-born folk of some of the bad reputation alleged by the song and pronounced country people who had made good their standing in Dublin for a few years, to be the greatest cheats in the kingdom.

Mr. Edmond, having now a right to call someone up, summoned Joanna, the servant maid, previously mentioned, to show what she could do. Joanna, though very ready with her tongue at home, was at heart a modest girl, and fought hard to be let off. But one protested that she was a good singer, in right of a lark’s heel she had, but this was not the case, for Joanna had a neat foot. Another said that she was taught to sing by note when Tone, the dancing-master made his last round through the country, another said, that he heard herself and a young kid sing verse about one day when nobody was within hearing.

So, poor Joan, to get rid of the torment, asked what song they would like her to sing for them, and a dozen voices requested a love song about murder. So, after looking down, with a blushing face, for a while, she began with an unsteady voice, but she was soon under the influence of the subject and sung with a sweet voice one of these old English ballads, which we heard for the first time from a young woman of the Barony of Bardon, in the south.

There is another song on the same subject in some collection which we cannot at this remember at this moment. But Joanna’s version is evidently a faulty one. It has suffered from transmission through generations of negligent vocalists and now it is not easy to give it an original period of time.

“FAIR ELEANOR.

“‘Come, comb your head, Fair Eleanor,

And comb it on your knee,

And that you may look maiden-like

Till my return to thee.’

“”Tis hard for me to look maiden-like,

When maiden I am none:

Seven fair sons I’ve borne to thee,

And the eighth lies in my womb.’

”Seven long years were past and gone.

Fair Eleanor thought it long.

She went up into her bower,

With her silver cane in hand.

“She looked far, she looked near,

She looked upon the strand.

And it’s there she spied King William a-coming,

And his new bride by the hand.

“She then called up her seven sons,

By one, by two, by three.

‘ I wish that you were seven greyhounds,

This night to worry me! ‘

“‘Oh, say not so our mother dear,

But put on your golden pall,

And go and throw open your wide, wide gates,

And welcome the nobles all.’

” So, she threw off her gown of green.

She put on her golden pall,

She went and threw open her wide, wide gates,

And welcomed the nobles all.

” ‘ Oh, welcome, lady fair! ‘ she said.

‘ You’re welcome to your own.

And welcome be these nobles all

That come to wait on you home.’

” ‘ Oh, thankee, thankee, Fair Eleanor!

And many thanks to thee.

And if in this bower I do remain,

Great gifts I’ll bestow on thee.’

” She served them up, she served them down,

She served them all with wine,

But still she drank of the clear spring water,

To keep her colour fine.

“She served them up, she served them down.

She served them in the hall.

But still she wiped off the salt, salt tears,

As they from her did fall.

” Well bespoke the bride so gay,

As she sat in her chair—

‘And tell to me, King William,’ she said,

‘ Who is this maid so fair?

” ‘ Is she of your kith, ‘ she said,

‘ Or is she of your kin,

Or is she your comely housekeeper

That walks both out and in’

” ‘ She is not of my kith,’ he said,

‘ Nor is she of my kin.

But she is my comely housekeeper

That walks both out and in.’

‘\’ Who then was your father,’ she said,

‘ Or who then was your mother 1

Had you any sister dear,

Or had you any brother 1 ‘

” ‘ King Henry was my father,’ she said,

‘ Queen Margaret was my mother,

Matilda was my sister dear,

Lord Thomas was my brother.’

” ‘ King Henry was your father,’ she said,

Queen Margaret, your mother,

1 am your only sister dear.

And here’s Lord Thomas, our brother.

” ‘ Seven lofty ships I have at sea,

All filled with beaten gold.

Six of them I’ll leave with thee,

The seventh will bear me home.’ “

The usual interruptions arising from new visitors entering had occurred several times during these relaxations, with the last visitor being a young giant of a man called Tom Sweeney. He was a labourer on the farm of young Roche, and an admirer of the songstress of Fair Eleanor, who, if she returned his affection, took special care to conceal the fact from the eyes of their acquaintance. Tom was as naïve a young man as there was anywhere in the county, and Peter O’Brien called on him to give a song. But the young man could think of nothing else to sing but the lamentation of a young girl for the absence of her lover.

” THE SAILOR BOY.

“‘Oh, the sailing trade is a weary life.

It robs fair maids of their hearts’ delight,

Which causes me for to sigh and mourn,

For fear my true love will ne’er return.

“’The grass grows green upon yonder lea,

The leaves are budding from ev’ry spray,

The nightingale in her cage will sing

To welcome Willy home to crown the spring.

“’ I’ll build myself a little boat.

And o’er the ocean I mean to float:

From every French ship that do pass by,

I’ll inquire for Willy, that bold sailing boy.’

“She had not sailed a league past three

Till a fleet of French ships, she chanced to meet.

‘ Come tell me, sailors, and tell me true,

If my love Willy sails on board with you.’

“‘Indeed, fair maid, your love is not here,

But he is drowned by this we fear.

‘It was your green island that we passed by,

There we lost Willy, that bold sailing boy.’

“She wrung her hands and she tore her hair

Just like a lady that was in despair.

Against the rock her little boat she run—

‘How can I live, and my true love gone? ‘

“Nine months after, this maid was dead,

And this note found on her bed’s head.

How she was satisfied to end her life,

Because she was not a bold sailor’s wife.

“‘Dig my grave both large and deep,

Deck it over with lilies sweet,

And on my headstone cut a turtledove,

To signify that I died for love.’ “

It is probable that the sentiments of this ballad will not produce similar feelings in our readers. It was not the case with the younger portion of Tom’s audience, for he sung it with much feeling. He was, indeed, a sincere young fellow, besides being a lover.

It would be a little boring, except to those with an interest in such things, if I was to let you read many more of the songs which were sung there. If truth be told, there were few that could be distinguished by them possessing genuine poetry or good taste. The people who were there were not so lucky and had to hear “The sailor who courted a farmer’s daughter, that lived convenient to the Isle of Man.” That was followed by the merry song called “The Wedding of Ballyporeen,” which caused the audience to laugh loudly, although they had heard it many times heard before. Then there were popular tunes such as, “The Boy with the Brown Hair,” “The Red-haired Girl,” “Sheela na Guira,” and “The Cottage Maid.” Laments and Ballads about lost loves and promising romantic futures, which were popular and encouraged the audience to join in. But, at last, some of those gathered began to demonstrate by their manner and gestures, that they had heard enough sweet singing, and O’Brien, and Roche, and Redmond, were invited to get up and perform the wake-house drama of ‘Old Dowd and his Daughters’, which would help them to hold out against the stale air in the room and the want of sleep.

The young men did not exhibit too good a sense of the moral fitness of things, since they were not normally disposed to vice, in private or in public. It was custom that influenced them to think that what was harmless at other times and in other places could be looked on as harmless at a wake. So, Charles at once assumed took his place as stage manager and assumed the role of Old Dowd with a daughter he needed to dispose of. He set the blushing and giggling Joanna on a chair beside him, Tom Sweeney, and two or three other young men on a bench at his other side, cleared an open space in front, procured a good stick for himself and each of his sons, and awaited the approach of the expected suitor.

O’Brien and Roche had gone out, and on their return were to be looked on, the first as the suitor, a caustic poet, who makes himself welcome at rich farmers’ houses by satirizing their neighbours, and the second as his horse, whose forelegs were represented by the man’s arms, and a stool firmly grasped in his hands. Roche’s election to this role was determined by his size and great strength. Finally, amid the most profound silence the performance of “Old Dowd and his Daughters” began—

OLD DOWD AND HIS DAUGHTERS.

[Present: Old Dowd, his marriageable daughter, Sheela, and his six sons. Enter poetic suitor, appropriately mounted. Father and sons eye the pair with much contempt.]

Old Dowd: Who is this, mounted on his old carthorse, coming to disturb us at this hour of the night? What kind of a tramp or traveller are you? for I don’t think we can give you a lodging, sir, and you must go on farther.

Suitor: I’m not an honest man, no more than you are yourself, you old sinner, and I don’t want a room. I’m seeking a cure for life’s troubles. In plain words, a wife who can be with me for the rest of my life on this earth. Are you lucky enough to be able to help me, for you won’t ever get another chance to make a more high-bred connection as myself? My grandfather owned seven townlands, and let more property slip through his fingers than the whole seed, breed, and generation of the Dowds possessed since Adam was a boy. Come on, are you ready for me?

Father of Bride: Aye, and what property have you got?

Suitor: A lawsuit that’s to be decided on day before Christmas Eve. If I gain it, I’ll get fifty acres of land on the side of the mountain at a pound an acre. If I lose, they can only put me in the jail. Come on, now, let us see the bride. But, first, as they used to say at the siege of Troy, let us know your breeding and bloodline.

Father. Here I am, Old Dowd, with his six sons. Himself makes seven, four more would be eleven, and hurrah, brave boys.”

At this point of the conference the patriarch flourished his stick, and aimed a few blows at the steed and rider, more, however, in courtesy than resentment. The suitor warded the strokes with some skill and gave a tap or two to his father-in-law elect. He at last setting his weapon upright and the argument ceased.

Father: Come now, I see that you are not altogether unworthy to enter the family of the Dowds. What’s your profession? How do you earn your bread? I won’t send out my dear Sheela to live on the neighbours.

Suitor: I’m a poet and live by the weaknesses of mankind.

Father: Och, what kind of trade is that? Your coat is white at the seams. Is that some sort of vest or is it a real shirt you have on you? How many meals a day do you get? Everyone knows the saying, ‘as poor as a poet’.

Suitor: Then I think three-quarters of the people about here must be in the same trade. If you were to be a father-in-law to me, then learn to be mannerly, Old Dowd. I scorn a vest, except when my old shirt is worn out, and my new one has not come from the seamstress, and if I could find an appetite, I might eat seven meals a day. I stop at a gentleman- farmer’s and repeat a few verses that I said for against a neighbour for his stinginess to one of the old-stock of the Muldoons, and a poet besides. And don’t myself and my steed live like fighting cocks, and the man of the house not daring to sneeze for fear of getting into a new a bad verse about himself. Is this my bride? Oh, the darling girl, I must make a verse in her praise off the top of my head, for if I was Homer, that noble poet, I’d sing your praises in verses sweet. Or Alexander, that bold commander, I’d lay my trophies down at your feet.”

“Venerable head of the Clan Dowd, my intended looks a little hot. I hope it wasn’t with the pot-rag she wiped her face this morning. Old Dowd, you’ll have to shell out something decent for soap. The young lady’s name is Sheela, you say. She’s not the same Miss Sheela, I hope! You know that Pat Cox, the shoemaker, was lately courting?

Father: You vagabond of a poet, do you think I’d demean the old kings of Leinster, my forefathers, by taking into my family a greasy shoemaker?

Suitor: I only asked a civil question. Pat met his darling one day, as she was binding after the reapers, and asked when she’d let him take her measure for a pair of new shoes. “No time like the present time,” says she, and off she kicked her right foot pump. Her nails were a trifle long and her lovely toes were peeping out through the worsted stockings. If there was anything between the same toes it wouldn’t be polite to mention it. So bewildered was the love-sick fool by the privilege conferred on him, that he felt in his own mind, that a prolonged communication would not be good for the peace of heart. So, the shoes are not yet made, and Pat’s nearest residence is in the village of Derrymore.

Father: And do you dare, you foul-mouthed blackguard, to cast insinuations on the delicate habits of my dear child? Take this for your reward.

Sympathetic Sons: And this … and this.”

And now began a neat cudgel-skirmish between the main contracting parties. The angry father not only struck at the evil-tongued suitor, but also whacked at the inoffensive horse. The suitor warded the blows from his trusty horse as well as he could, but still one or two made impressions on the more sensitive portions of his body, and the sons with their wooden sticks added to his overall discomfort. So, the noble animal, feeling his patience rapidly diminishing, executed a half-jump, and applying the hoof of his off hind leg to the bench on which the old gentleman and his sons were sitting in state, he overturned them with little effort, and their heads and backs made sore acquaintance with the wall and floor.

This disagreeable incident, and the still unconquered difficulties, stopped the further prosecution of the suit, and amid rubbing of sore spots, scratching of heads, and howls of laughter from all parts of the room, they set about another match with Peter’s grand-daughter being obliged to sit for the next blushing bride. In this second act, Redmond came in as a wooer, bestriding Tom Sweeney, His cue was to have nothing of the poet or the vagrant hanging to his skirts. He was the miserly, careful tradesman of country life. O’Brien represented Old Dowd.

Thrifty Suitor: God save all here! Look here, I want a wife, and no more about it. Have you got one available?

Father: To be sure we have! Who are you if you please?

Thrifty Suitor: I’m not ashamed of my name nor of my business. I’m a brogue-maker to my trade, and my name’s Mick Kinsella, and I’m not short of a few pounds in my pocket, not like that scare-crow, Denny Muldoon, that’ll be obliged to throw his large cloak over his bride to keep her from freezing with the cold in the honeymoon. I won’t have Miss Sheela; you may depend on it.

Father: Indeed, I think you’re right, Mick-the Brogue. That dear girl was a little untidy, still she wasn’t without her good points. But she would persist in wiping the plates with the cat’s tail when the dishcloth was not at hand, and I’m afraid that her husband won’t be known by the whiteness of his shirt collar at the chapel. Well, well, we won’t speak ill of the absent. But here, you son of a turned pump, is the flower of the flock for you. Here’s one that will put a genteel stamp on your stand of brogues at a fair or market. By the way, the shoemakers don’t associate with you, men of the leather strip. They don’t look on you as tradesmen. What shabby pride! Begging your pardon, Mick, what property have you, and what do you intend to leave to your widow? After all, no one can say to your face that you married out of a frolic of youth. You’re turned fifty, I think.

Thrifty Suitor: No, I am not, Old Dowd! I am only pushing forty-five, and I have neither a red nose nor a shaky hand, Old Dowd. And I hope Mrs. Kinsella won’t be at the expense of a widow’s cap for thirty years to come, Old Dowd. But not to make an ill answer, I have three hundred red guineas under the thatch. And now tell me what yourself will lay down on the nail the day your daughter changes her name.

Father: Well, well, the impudence of some people stings! Isn’t it enough, and more than enough, to get a young woman of birth, that has book-learning and reads novels? And you, you big jackass, don’t you think but your bread will be baked the day she condescends to take the vulgar name of Kinsella? Why, man, the meaning of the word is “Dirty Head.” An old king of Leinster got it for killing a priest.

Thrifty Suitor: I don’t care a pig’s bristle for your notions and grand ideas. Give me an answer if you please.

Father: Oh, dear, dear, Old Dowd! Did you ever think you would live long enough to hear your genteel and accomplished daughter, Miss Biddy Dowd, called by the vile name of Biddy -the-Brogue?

Thrifty Suitor: Now, none of your impudence, you overbearing and immoral old toper! I want a wife to keep things snug at home, and make me comfortable, and not let me be cheated by my servants and workmen. You say that Biddy reads novels and, maybe when the ploughmen come in at noon, they’ll only find the praties put down over a bad fire, and the mistress crying over a greasy-covered book in the corner. To the Devil with all the novels in the world.

The Dowds (father and sons): This ignorant gobshite never went as far as the “Principles of Politeness ” in the “Universal Spelling-book.” Let us administer the youth a little of hazel-oil to make his joints supple and teach him some manners!”

Then another battle of arms took place, in which some skilful play was shown with the sticks, and several sound thumps were given and received, to the great delight and edification of the assembly.

Thrifty Suitor: Now that these few compliments are over, what is to be the fortune of Biddy, I beg a thousand pardons, Miss Biddy Dowd, I mean?

Father: Isn’t her face fortune enough for you, you vulgar man? Do you think nothing of the respectability of having her sitting on a pillion behind you going to fair or market to work after you, with her green silk gown and quilted purple petticoat, and her bright orange shawl? Ah, you lucky thief! Won’t you have the crowd of young fellows around you, bargaining for your ware, and inviting Mrs. Kinsella to a glass of punch? I think, instead of expecting a fortune, you should give a big bag of money for being let into my family.

Thrifty Suitor: Old Dowd, all your bluster isn’t worth a cast-off brogue. Mention a decent sum, or back I go to my work. I’m young enough to be married these fifteen years to come.”

Here the father and sons put their heads together, and finally the hard-pressed father named twenty pounds, but the worldly-minded suitor exclaimed against the smallness of the sum and insisted on a hundred. After a series of skilful thrusts and parries, they agreed to split the difference, and the candidate was asked whether he preferred to receive it in quarterly payments or be paid all at once. He inconsiderately named present payment and had soon reason to repent of his haste to become rich, for the dowry descended on himself and his charger in a shower of blows from the tough hazels and blackthorns of his new relatives. After receiving and inflicting several stripes, he shouted out that he was satisfied to give a long day with the balance. And so, with their shoulders and sides sore with blows and laughter, the play came to an end, and much appreciation was shown by the audience both with the action and dialogue, for many in the crowd knew the parties who were represented, and scarcely, if at all, caricatured. Denny Muldoon, and Mick Kinsella, and Biddy-the-Brogue, were well-known under other names.

When the enthusiasm had subsided a little, it being now about one o’clock in the morning, O’Brien, Roche, Edmond, Joanna, and Sweeney withdrew, but not before reciting some prayers before they left the room. When the vacated seats came to be filled, and lately bashful young fellows began to use the tobacco-pipes, which one but the older folk had meddled with before, the hitherto tolerably decent spirit of the society began to evaporate, and confusion and ill manners began to prevail. However, a young fellow, who felt a desire to hear himself sing in company, got some of his supporters to endeavour to quieten the noise, and request him to favour the assembly with a song. The noise did not entirely subside until the first notes were heard, and the dismal style in which the verses were sung needed to be restrained but indifferently.

” THE STREAMS OF BUNCLODY.

“Was I at the moss-house where the birds do increase,

At the foot of Mount Leinster, or some silent place,

At the streams of Bunclody, where all pleasures do meet,

And all I require is one kiss from you, sweet.

” The reason my love slights me, I do understand,

Because she has a freehold and I have no land.

A great store of riches, both Silver and gold,

And everything fitting a house to uphold.

“If I was a clerk who could write a good hand,

I’d write to my true love that she might understand,

That I’m a young man that’s deeply in love,

That lived by Bunclody, and now must remove.

” Adieu my dear father; adieu my dear mother.

Farewell to my sister, and likewise my brother.

I’m going to America, my fortune to try.

When 1 think on Bunclody, I’m ready to die.”

The general feeling at the time was too cynical to relish such a sad song. Several songs were sung, whose composers’ ghosts shall not have the gratification of seeing them here either in substance or name. At last, even the songs, such as they were, began to lose their charm, and games were introduced. The first was played in the following way –

The captain took five assistants, and arranged them in a semicircle, giving to each a name. He then began with a short stick to pound the palm of one to whom the mischance came by lot, keeping a firm hold of his wrist all the time, and naming the troop in this manner “Fabby, Darby Skibby, Donacha the Saddler, Jacob the Farmer, Scour-dish, what’s that man’s name?” He suddenly pointed to one of the group, and if the patient named him on the moment, he was released, and the fellow named was submitted to the handy discipline. If there was the slightest delay about the name, the operator went on as before—”Fibby Fabby, Darby Skibby,” etc., until the poor victim’s fingers were in a sad state.

In the second game a candle was placed on the ground, in the middle of a circle of lads, and all are told to keep their eyes fixed on it, and their hands behind their backs. The captain provided himself with a twisted leathern apron, or something equally unpleasant to be struck with, and walked on the outside of the ring, exclaiming from time to time, “Watch the light, watch the light.” Secretly placing the weapon into the hands of one of the men, he at last cried out, “Use the linger, use the linger;” and this worthy ran round the circle, using it to some purpose on the backs of his playmates. He then became the captain, and in due course delivered the instrument to someone else.

But the most objectionable trick of all was “shooting the buck.” Some person or persons who had not yet seen the performance were essential to its success, as it required a victim or two. The person acting the buck having gone out, the sportsman who was to shoot him required one to three unsuspicious persons to lie in wait inside the door, to catch the animal when falling from the effect of the shot, promising that they should see fine things. All became silent and watchful, and the retrievers were at their post, when the stag appeared in the doorway, a stool on his head, with the feet upturned to represent horns. The huntsman stooped, and squinting along a stick, cried out, “too-oo”! Back fell the animal, and down came the stool, and all the dirt with which the rogue had charged it outside, on the hats and clothes of the raw sportsmen, and great laughter rose from all the throats but theirs.

By this time, it is three or four o’clock, and time for anyone who dreads the terrors of an over-burdened conscience, while he lies passive and stretched out the next morning, to quit the scene of such frivolity. We might here moralize on the inherent evil of the institution, and the number of young men who became hardened in vice by attending wakes, and the number of young women who lost their character thereby, and everything with it, here and hereafter. The evil lay in visiting them at all, for more than a few minutes. It would be out of the question for the best-intentioned to remain in the foul room for the whole night and come out as innocent in the morning as they entered in the evening. Girls with any pretence to good conduct never remained in them beyond the early hours of the night and were always supposed to be there under the guardianship of a brother, cousin, or declared lover. We will say, for the honour of those districts of Ireland that were known to us, that it was rare to hear of a young woman, farmer’s, or cottager’s daughter, of bad character.