One Perspective

Ireland is well-known for its whiskey, its Poitin, Turf, Storytelling, the Music and the Craic. But, as well as the remote mountains, peat bogs, lakes, and country roads, there is the sight of Irish Travellers, who make up just under 30,000 people or one percent of the country’s population. Being a ‘Traveller’ is a recognised status within Ireland’s social strata, and to be considered a member of the ‘Traveller’ community an individual must have at least one ‘Traveller’ parent. What is also striking about the ‘Traveller’ community in the country is that they have their own language, formally known as ‘Shelta’, which the ‘Travellers’, themselves, call ‘Gammon’ or ‘Cant’. An analysis of ‘Shelta’ has led some scholars to conclude that it came to the fore when the use of the Irish language was prohibited by English conquerors, some 350 years ago.

Although a distinct nomadic group of people they are in a unique position in Ireland because the ‘Travellers’ are native to this land. Over the centuries they have had to face many internal and external influences working against them, which have left their present sociological status is a precarious condition. They have been considered a ‘problem’ by many generations of Irish men and women and have had to suffer repression, suppression and discrimination to varying degrees, leaving them be currently viewed by many in ‘settled’ population as second-class Irish citizens.

The true origins of Irish Travelling People is a continuous source of debate in Ireland, but four main causes behind how ‘Irish Travellers’ came into being. One theory suggests that their direct descendants became nomadic for some economic, social, or cultural reason that caused them to prefer living outside the ‘Brehon Laws’, which were an ancient body of ‘Common Law’ dating from pre-historic times in Ireland. The wandering habits of the people within Gaelic Ireland have also been advanced as a possible explanation for nomadic metalworkers or ‘plain tinkers’. Some researchers have emphasised the mobile, nomadic nature of Gaelic society, believing that the suppression of this lifestyle during the sixteenth-century Tudor reconquest laid the colonial foundations of anti-Traveller racism. Despite such actions by the English elements of the Gaelic pastoral economy continued, the best-known example being ‘booleying’. This is basically the practice of people living in temporary shelters moving herds of cattle from winter to summer pastures. ‘Booleying’ is an important factor in the context of nomadism because it was an agricultural practice demanding seasonal movement that survived within Ireland in some form until the nineteenth century. Its persistence illustrates the difficulty of describing all agriculture as being carried out on settled farmland when the pastoral economy favoured by the Irish cattle farmer could be described as partly nomadic.

The theory that ‘Travellers’ emerged from such a nomadic population has three distinct aspects i.e. craftsmen, the poor and dispossessed, and social misfits. It is believed that craftsmen in metal work and their families were the original nomadic population, and date from the pre-Christian days in this land. A second theory suggests that the ‘Travellers’ are the direct descendants of native Irish chieftains who were dispossessed of their lands and property by the English during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, and ‘planted’ with English and Scottish protestant farmers. There is another theory that claims that the ‘Travellers’ were the result of intermarriage between the ‘Romany’ Gypsies and Irish peasants. However, it is more likely that the ‘Travellers’ are the descendants of peasants and labourers who were driven from their land by the political and economic upheaval caused by the Great Irish Famine (1845-1850).

In prior centuries, great poverty, Cromwellian wars, and dispossession, evictions and pressure upon the land all combined to produce ‘the crisis of the Irish peasantry’, which drove thousands to wander the roads of Ireland. Researchers have been very careful to say that it is not possible to put an accurate figure on the number of dispossessed tenants and labourers joined the ranks of itinerant craftsmen, and eventually became permanent Travellers. All that we have are theories even today we cannot accurately place their origin of ‘Travellers’ within a certain and credible historical context. Nevertheless, the scholars cannot resist making a link between contemporary ‘Traveller’ surnames and the poverty-stricken population of the west of Ireland, encouraged by the fact that we do know that forty percent of the ‘Travellers’ share ten common surnames.

Over the centuries, ‘Travellers’ became a separate group because they were permanently nomadic and were able to distance themselves from the numerous male tramps and vagabonds who were always on the roads in these times. This distancing other itinerant people is a strange contradiction, but it demonstrates that the similarity in their lifestyles was not the most important factor in bringing about the ‘Traveller’ population. This difficulty has only added to the problems that scholars have had in placing ‘Travellers’ within the historical records as a distinct cultural minority. We cannot, therefore, presume that ‘Travellers’ in the past were the same as the ‘Travellers’ we know today. In the same way, the well-understood boundaries between ‘Travellers’ and settled people are evident in the recent past, based on family structure, work patterns, religious beliefs, and gender roles, cannot be presumed to have existed in earlier societies. Some researchers claim that after the end of the ‘Great Famine’ in 1850, the antipathy which is shown in present-day attitudes towards itinerants appears to have begun to develop’, although there is little evidence to support such a claim. But we do know that life in twenty-first century Ireland is as different to the Ireland of the mid-nineteenth century as it is to the Ireland of the ninth century.

The ‘Travelling People’ are so much a part of Ireland today, but we cannot definitively state that they emerged as a result of dispossession, and colonial oppression. Historians have not directly blamed Anglo-Irish relations for the existence of homeless individuals and families who subsisted on begging and seasonal employment. However, epidemic disease, the lack of organised welfare, economic crises, poor harvests, and demobilisation do seem to feature as causes. Local studies of efforts to improve the status of the homeless poor do show that institutional confinement was the method most favoured by eighteenth-century society. But, since there was no statutory, nationwide system of poor relief in Ireland until 1838, urban and rural dwellers who could not earn or produce enough to support themselves frequently resorted to begging and vagrancy.

Although the ‘Travelling’ population in Ireland was large, contemporary observers did not see it clearly as a separate grouping of people. However, research into Irish attitudes to poverty before 1838 shows that most are attempts by society to differentiate between the men, women, and children who travelled the roads seeking work or alms. In eighteenth-century Dublin, those with money and authority attempted to ‘devise specific types of responses to the different types of pauper which they believed existed. These distinctions were made on the basis of origin, health, ability to work, age, gender, and religion. But even within these categories, there were further differences, causing more attempts to better understand the homeless population and a long list of different terms to describe them, including strange beggar, local beggar, habitual beggar, foreign beggar, stroller, mendicant, vagrant, vagabond, badged poor, impotent poor, sturdy poor, idle poor, church poor, foundling. The number of terms and the subtleties of meaning conveyed by their varying uses in different contexts suggests that there was a complex attitude to the homeless in those days. It is not possible for us to say whether the extent of differentiation between the poverty-stricken people included any notice being taken of culturally distinct nomads as separate from, or in addition to, the various categories of homeless poor. However, since the researchers of the time were primarily interested in describing people with no fixed abode who begged for alms, the cultural life of these individuals would have held no importance.

In years past the ‘Traveller’ would be well-known for story-telling, word-of-mouth histories and they travelled from place to place singing, playing music, and telling stories to entertain people. More importantly, however, for the more isolated Irish communities, these itinerants provide a useful social function in bringing the news with them. As their name suggests the ‘Travellers’ were habitual wanderers, moving from place to place and having no fixed abode that they could call home. In more recent times, however, such a definition neglects to include those partially settled travellers who have elected to live in houses, as opposed to Campsites or Halting sites. Nevertheless, their nomadic inclinations remain a key part of the culture of the ‘Travelling People.’ But, even in years past, mobility was not something that was confined to the destitute but was a relatively common feature of agricultural and urban work. Apart from the ‘Booleying’ that has been mentioned, labourers travelled to gather the harvest, and there was an annual migration between Britain and Ireland of labour, which has been well-studied. However, little is known about the internal migration patterns of seasonal labourers in Ireland, who travelled between certain counties or areas on a regular basis. Although Irish agriculture may not have required as many seasonal workers as the farms of England or Scotland, harvest time continued to generate a demand for labour that could not be met by farmers’ families or the local labour force.

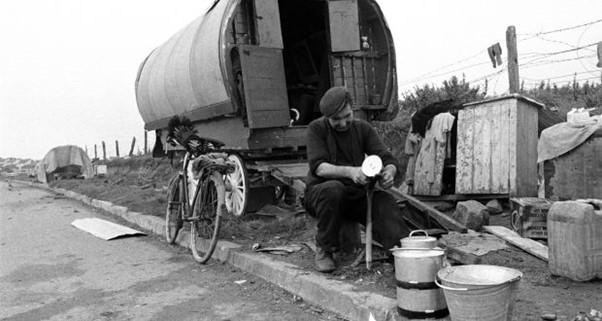

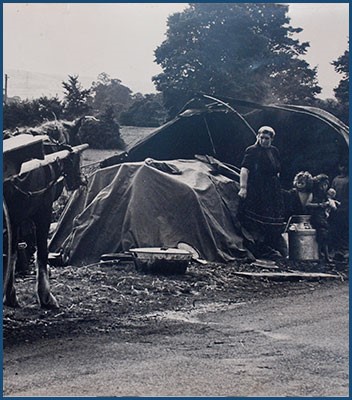

Seasonality and its attendant mobility persisted even in industrial occupations. People in the cities and towns also left their fixed homes to become seasonal agricultural labourers, while men employed in the building trade tramped for miles to secure work. The scholars would divide these ‘migrating classes’ into four separate categories, based on the extent and patterns of their mobility. In the first group, there were habitual wanderers who possessed no home base. Second, there were those who spent a large part of the year on country roads, but who kept regular winter quarters in the town. Thirdly, some were ‘fair weather’ travellers, who travelled only in the summer, but stayed in one place for the remainder of the year and, finally, some travelled frequently on short trips to the country, never travelling far from their home. The same scholars point out that the Gypsy population could be similarly differentiated, with some groups having very limited seasonal travel circuits. Today, however, the customs and habits of ‘Travellers’ are, for the most part, at variance to those of the settled population within whose midst they live. Not surprisingly, these differences have often been deliberately misinterpreted by certain sections of the main population, which has resulted in ‘Travellers’ being left isolated on the margins of mainstream society. Moreover, despite advancements among the ‘Traveller’ communities, many continue to suffer from a range of social, health and economic problems. In most cases, they have no direct access to piped water or plumbed toilets. They also suffer the consequences of holding few or no educational qualifications, particularly due to the unfortunate fact that their children are the most likely to suffer social intolerance. Added to these factors, it has been noted that ‘Travellers’ have a high mortality rate. Statistics suggest that a ‘Traveller’ woman lives twelve years, nine years for a ‘traveller’ man when compared to the general population of the country.

There are many within the general population who cannot understand why the ‘Travellers’ have been granted ethnic status by the Irish Government. When one considers ethnicity, this would naturally include national, racial, religious or language differences. But when compared to the settled population of the country all such traits are very similar. There is very little, if any, difference in the way both communities physically appear. They speak English and count themselves as practicing Catholics, which is also in line with the majority settled population. Their uniqueness, therefore, is more subtle than simply skin colour, religion or language, and may lie in their history.

Although they make up only one percent of total national people, the ‘Travellers’ have very high visibility because of their practice of living in caravans by the roadside. This ‘high visibility’ factor and nomadic lifestyle appear to have made the ‘Travellers’ the least likely minority grouping in Ireland to be made welcome by the settled population in either the urban or the rural, setting. Although essentially native to Ireland and having a heritage that is intertwined with Irish history, as a social group, ‘Travellers’ continue to be regarded as second-class Irish citizens by many within the dominant or ‘settled’ population.

In years gone by the traditional way of life in Ireland allowed ‘Travellers’ and the ‘settled community’ to live under a system of mutual tolerance. Historically, Irish dependency on agrarianism and farming created an economic need for migrant labourers in particular areas, and ‘payment in kind’ became the norm. A ‘Traveller’ man would call to a farm, work there for the day and be given food and a place to sleep for the night. The Industrial Revolution, however, would wreak havoc on the traditional trade of ‘Travellers’ and resulted in little work coming into their community. Machinery and efficient methods gradually caused the economic gap between Travellers and settled people to be widened considerably since this period. Moreover, what the ‘Traveller’ defines as employment is not what is traditionally considered as employment by the dominant population. The arrival of the ‘Welfare State’ and the benefits available to the unemployed, large families, disabled, sick, or disadvantaged saw an increase in Traveller uptake of these benefits. At the same time, they would continue working on whatever manual jobs came their way.